God became a man.

Just in case, the enormity of that last statement didn’t overwhelm you, allow me to repeat myself.

The eternal omnipotent deity came into the world as a breathing, eating, sleeping, pain-feeling human being.

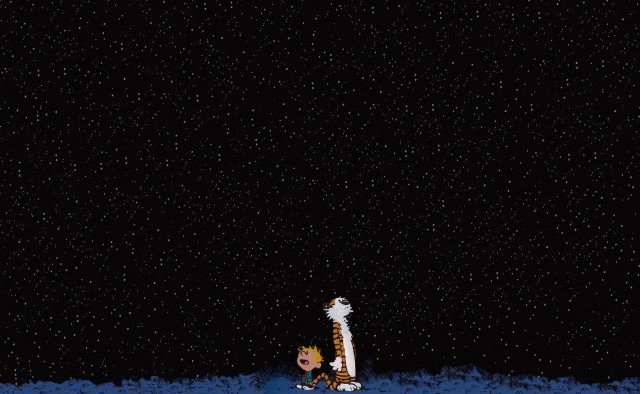

That this affirmation doesn’t shock or astonish us is an indication of how much our theology/churching has gone wrong. We’ve grown so familiar with the idea that it nearly sounds trite. This is what more or less occupies the whole of Barth’s chapter on ‘Wonder’. In Jesus Christ, God has done something new and unimaginable. And yet, so often it neither sounds new nor does it exercise our imaginations very much.

It is worth noting, that this ‘wonder’ is radically theological in character. It isn’t the more generic wonder with the world in general. This latter sort of wonder is one that finds its moorings in modern romantic preoccupations with the world available to us through our senses. While there is undoubtedly much to hold in awe within the created order, there are disastrous theological consequences for too easily eliding the wonder of creation with the wonder of the Creator. It tempts a confusion that can effectively result in a collapse into pantheism. Which is ok if you that the direction one wants to go, but let’s be honest about where we’re heading.

The wonder Barth has in view here is more narrowly focused on the sort that is occasioned by a finite being’s attempts to comprehend, in any measure, that which is infinite. The theologian (professional or otherwise) who makes any attempts at this task will either find themselves quickly (or eventually) confronted with the impossibility of the task or they will rush headlong into something that is, in fact, non-theology. Perhaps another way of saying the same thing, the moment we cease to approach the work of thinking and speaking about God without a sense of awe and humility, we are doing something other than theology. By definition, thinking after a God who is entirely ‘other’ is an infinite task and is (joyful) work that can never be exhausted.

One response to the eternal mystery of God is to simply acknowledge the impossibility of saying anything definite about that which is wholly other, and therefore give up the endeavor completely. Yet, the Christian message is one that affirms in no uncertain terms that God – this infinitely ‘other’ God – makes himself known. Even our affirmation that God is infinite, mysterious, or awe-inspriing, etc… is itself a God-given knowledge, because for Barth all theological truth is God-given truth. Even the bits that we think we could have come up with on our own. Or as the quote below suggests, it is because we have been met by God at all that we know him as mystery.

Mystery is the concealment of God in which He meets us precisely when He unveils Himself to us, because He will not and cannot unveil Himself except by veiling Himself. Mystery thus denotes the divine givenness of the Word of God which also fixes our own limits and by which it distinguishes itself from everything that is given otherwise. (CD I/1, p. 165)

According to Barth, if we don’t encounter God as mystery, then we simply haven’t encountered God.

We’ve left the chapter at hand and are venturing away from the shallow end of the pool, but maybe the thing to hold on to from the present chapter is Barth’s belief that to be engaged in theology will necessarily involve a sense of wonder. Not simply (or even primarily) about the reality we are able to perceive through our senses, but a wonder for one who exists outside and yet upholds that reality.

“Kids think with their brains cracked wide open; becoming an adult, I’ve decided, is only a slow sewing shut.” Jodi Picoult