I know this is suppose to be a Friday thing. I wanted to get it done on Friday, but it just wasn’t meant to be. A number of the books I read in 2011 were honestly pretty forgettable. However, there were a few that stirred the heart or mind (sometimes both) enough for me to recommend them to others. They are all of the “religious” variety. I’m not apologizing for that, but I just want to be clear about what you can expect.

Transforming Conversion: Rethinking the Language and Contours of Christian Initiation

Transforming Conversion: Rethinking the Language and Contours of Christian Initiation

by Gordon T. Smith

(sample chapter)

If there is one book that I’ll be re-reading in 2012, it will be this one. Smith’s work on conversion is thought-provoking to say the least. If you are one cares about what the journey of faith (particularly what we call “conversion”) looks like, then I can’t more highly recommend this book. Like a good physician, Smith adeptly diagnoses what ails modern day evangelicalism. His ideas on how we might restore health don’t feel quite as thought through, but his insights are difficult to dismiss lightly. If nothing else, read the sample chapter and see if he doesn’t pique your interest. Plus I would really love to have someone to talk to about what he has to say.

Without doubt, the greatest problem with the assumption that conversion is punctiliar is that it rarely ever is. Many people do not have a language with which to speak meaningfully about their own spiritual experience for the simple reason that they have not experienced conversion as a punctiliar event in their lives. Whether they are second-generation Christians (more on this below) or whether their journey to faith and of faith does not fit the mold, they do not know how to tell their story, how to give expression to their encounter with God’s grace.

Movements of Grace: The Dynamic Christo-Realism of Barth, Bonhoeffer, and the Torrances

Movements of Grace: The Dynamic Christo-Realism of Barth, Bonhoeffer, and the Torrances

by Jeff McSwain

(sample chapter)

Movements of Grace came my way from my father-in-law who got it from my brother-in-law who is friends with the author. So that pretty much makes me and the author best friends. As is often the case, titles can be misleading which is why we need subtitles. In fact, subtitles all the way through the book could be helpful given its dense theology – which can at times sound like a foreign language. In some ways, this book is similar to the previous one in that they are both concerned with how God’s work happens in person’s life. Both suggest that modern-day American evangelicalism places too much emphasis on human volition as the precursor for God’s saving activity. When I finished, I had a greater appreciation for and understanding of trinitarian theology. It also caused me to go back and re-read Barth, and that’s probably a good thing. From what I understand McSwain was embroiled in some controversy with Young Life a few years ago, and reading this book certainly helps one understand why that might have developed.

For my years of Christian ministry before January 2000, I habitually proclaimed the gospel in a way that undervalued the union of Jesus Christ with both God and humanity. On the one hand, while I pad lip service to the fact of Christ being God, my articulated theory of the atonement defied it. I portrayed a God who sent Christ to assume the world’s sin so that God could stay pure in himself.

Love Wins

Love Wins

by Rob Bell

(sample chapter)

Speaking of controversial books, you might find the inclusion of Bell’s Love Wins on the list surprising. Honestly, there were several other books that I found more interesting than this one, but there is no denying that it created quite a splash – even before it was released. There is also no denying that the conversation concerning universalism is still alive and well. Let’s be clear, Rob Bell didn’t invent universalism (he isn’t even a true universalist). He simply moved the discussion from people’s living rooms into the church, and I think the discussion has by and large been a healthy one. Bell is particularly gifted at asking questions, and in a way he is only asking the same question (albeit in a different way) that the previous two books are asking – Who does “salvation” depend on? Me? Or Christ?

Really?

Ghandi’s in Hell?

He is?

We have confirmation of this?

Somebody knows this?

Without a doubt?

And that somebody decided to take on the responsibility of letting the rest of us know?

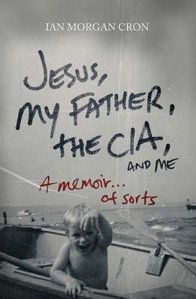

Jesus, My Father, The CIA, and Me: A Memoir… of Sorts

Jesus, My Father, The CIA, and Me: A Memoir… of Sorts

by Ian Morgan Cron

(sample chapter)

What is there for me to say about this book that I haven’t already said? I would simply like to add that this book in some ways falls in line with the other three. I quoted at length from his recollection of his first communion, and it is noteworthy that the ‘saving’ work was something that came from without, not within. I would love to quote more from this wonderful memoir, but I’m pretty sure that the author/publisher would hunt me down and demand some royalties. Of all the books on the list, this is easily the one that my vast readership would most appreciate.

So as you can see, a recurring theme in my reading this year has been on the way in which God works in people’s lives. In American church culture, we unsurprisingly place a great deal of emphasis on the choice of the individual for the efficaciousness of grace. Sure grace is a good gift of God, but it is something I can either choose to accept or reject. I’m coming to terms with (but far from having resolved) the notion that grace only becomes operative when I make a choice for it to be. Like I said, a very American sentiment. I’m just not sure how biblical it is. If grace only becomes saving grace through some choice of my own was it ever really grace to begin with?

Ok, enough heresy for one day. I really do love hearing what other people enjoy reading. Last time I did a book post, several people chimed in on things they appreciated. I’m especially indebted to the women who helped to broaden my appreciation for female authors. As you can see here, that is something of a deficiency in my reading diet, and I really would love to hear what sort of things you guys have found helpful recently.

Stay tuned for an honorable mention list sometime soon.