A brief reflection on my father written for a collection of essays presented at the 2012 ten-year memorial of his death.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Sons have always a rebellious wish to be disillusioned by that which charmed their fathers.”

Aldous Huxley

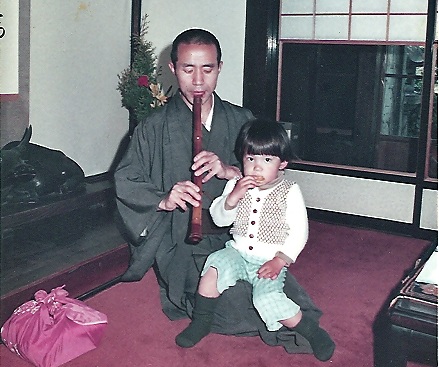

Like many young men who find themselves struggling to come into their own, I can remember making a commitment early in life to be nothing like my father. The list of things I intended to reject was a long one. I wanted none of his flaws, his temperament, his beliefs, his failures, his demons. So with reckless abandon, I attempted to purge all that was “Kobun” inside of me.

Yet, the passing years have confronted me with the truth that most adult children are forced to come to terms with eventually.

We are our parents.

And with the same inevitability as the downhill flow of water, it seems that each year takes me one step closer to resembling him, and not just in the face. In fact, the likeness may be least of all in physical appearance. Rather, it has been those characteristics that lie beneath the skin, and yet are so unmistakably recognizable, in which the similarity between father and son is most pronounced.

The more vivid memories of life with my father come from my adolescence during which time he was living in Taos. Every year, I would spend a number of weeks with him filled with leisurely days generally unstrained by his need to fulfill public expectations. Reflecting on these visits has been like looking into a window of a past life and having the chance to see him for the man he was outside of the public eye.

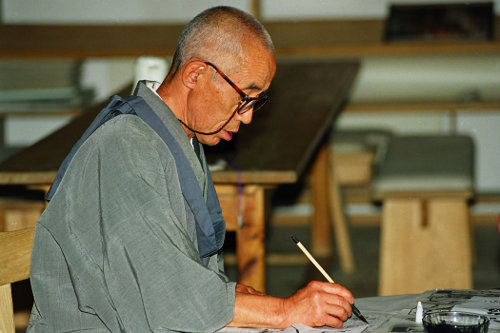

My father had a study in his home. Actually, I believe it was more of a large closet that was converted into a study. Inside the small room a zabuton and zafu were positioned in front of a low table. On and around the table were a collection of writing supplies, brushes, inks, paper, and lamps. But what dominated the space were his books. He had what seemed like thousands of books arranged in stacks, placed on shelves, resting on the table and under the table. There probably was a system, but it remained a mystery to anyone other than himself.

This small room was simultaneously his private zendo, library and art studio. And while he didn’t stay in permanent seclusion, it was not uncommon to find him toiling away over parchment, painting or tome at any time of day (or more often night). I used to think it strange that he would spend so much time cloistered away. Now I understand that there was something sacred about that tiny sanctuary, and I find myself attempting to re-create similar rhythms and spaces, hoping to find a small place of respite inside an otherwise busy home and an otherwise busy life.

If he wasn’t in the study, the next most likely place to find him was in the kitchen. He gave careful attention to the preparation of food and was a remarkably adept cook. Much like his religious beliefs, he took the cuisine of his ancestral heritage and adapted it for a new cultural setting. Rice was a non-negotiable, but it was always served with some other traditional Japanese dish that typically included some of his own improvisations.

Of all the food items he prepared, the “rice-ball” will be the one that remains forever etched into my memory. It’s simplicity, portability, and novelty has no rival. Anytime I was traveling some distance, without fail he would send with me a couple of seaweed wrapped balls of rice that were slightly larger than my fist. Which Japanese pickle I might find pressed into the center of this ball was always a surprise, but the pungent flavor of the umeboshi was undoubtedly my favorite.

While I believe he found great pleasure in giving himself to the mysterious intermingling of truth, beauty, routine service and compassion that was to be found in the study and kitchen, he seemed most at home with himself when he was outside enjoying nature. It mattered little whether he was spending a couple hours (or nights) bivouacked by his perpetually under-construction house, wandering the slopes of El Salto, or gracefully gliding down the snow covered mountainside. There was something about being close to creation that breathed life into him.

While my father enjoyed being with people in various settings, truth be told I think he found verbal communication taxing. He could be wonderfully clever and profoundly ambiguous all within the same breath, but in day-to-day life he could allow hours to pass with little to no talking. Indoors, silence can be strange. But under a canopy of trees, with the soft earth underfoot, being quiet seems the normal thing to do. Which is perhaps why he seemed more at home and more himself when he was outside.

“The joys of parents are secret, and so are their griefs and fears.”

Francis Bacon

These remembrances provide small glimpses into who my father was in the quieter “joys” of his every day life. In his study, he was able to pursue his curiosity as well as his creativity. Through his cooking, he expressed his routine daily care for the people in his life. Wandering the mountains, he was free to enjoy the beauty and majesty that a moment-in-time can afford. These things have become his legacy to me. While his joys remained a secret to me for a long time, it was not because they weren’t there to be recognized. The problem was my inability to recognize them. I have only recently been able to discover these things to be true about him through my recognition of the way these same pursuits have “charmed” me.

I suppose this means that I have now come full-circle (which I understand is a very Zen thing to do), in that I no longer strive to be unlike my father. I am growing in my recognition that while we are all tragically flawed in various ways, there is also much that is wonderful in each of us. One of the unfortunate consequences of focusing exclusively on the negative is that we miss out on the opportunity to embrace all that is good.

The Christian tradition of which I am a part makes much of the notion of grace. Indeed, many would say that it lies at the very heart of Christian teaching. That somehow, in and through the Christ, we can discover forgiveness for all the pain and suffering we inflict on others as a result of our brokenness and selfishness. It was this idea of forgiveness that drew me to Christianity over twenty years ago.

And yet, in the last decade this theological tenet has shifted from simply being an idea that is endorsed to a reality that is experienced. Through my openness to living in that grace-filled reality, I have come to recognize that my father is just like the rest of us. He (and I) are broken human beings in need of grace and forgiveness. And as much my father is in me, when I extend grace to him I discover that I am likewise extending it to myself.

“He will turn the hearts of the fathers to their children, and the hearts of the children to their fathers.”

Malachi 4:6

taido , …. your dad was/is my dharma brother. i was there. i knew you when you were so young; so open with such wide eyes.

i am so glad to hear where you are traveling now.

what i wish i could communicate is, like your dad, best shared in silence.

you are his dharma heir, albeit you wear different garb. this moves me deeply.

love always ~ always love ~ ” rishi “

Taido, this is beautiful. I read this today because of Alison’s post remembering the anniversary.

Hi Taido, I just discovered this site while looking for pix of your dad. I was one of the first people he ordained as a monk and studied with him intensively for six years, before moving to LA to train with a different teacher. This began around the time you were born in 1970 and continued until 1976, You and Yoshiko were often playing while your dad and I talked. We were very close–he was like an elder brother to me–and he asked me to take care of the two of you if anything ever happened to him. Fortunately, nothing did while you were young. I was in Hawaii when he died and could not attend the memorial. But I wrote a tribute to him, also titled “Remembering Kobun,” for Tricycle, the Buddhist magazine. I would be happy to send you a copy if you’re interested. Wishing you all the best, Steve Bodian

Dear Stephan,

Many thanks for your kind note. Always happy to hear from people who have fond memories of my father. I would be grateful to receive a copy of your article. Perhaps you can email it?

tjchino at gmail dot com

Blessings.

Dear Taido, and Yoshiko,

Please allow me to make an important correction to Carol Gallup’s “Remembering …” The only reason your father moved to Taos, New Mexico was to be within a day’s drive of you. He wanted to be as physically close to you as possible without causing interference in your daily lives. You were in his heart and prayerful mind at every moment. Likely still are.

It often seemed to me that although Japanese ideals were the same as American, the outward expression of them in behavior was frequently opposite. How confusing for you.

When asked what he thought of your grown-up lives, he replied that he was glad you could help people.

Like father, like daughter and son. Thank you for helping others, for sharing your father, and yourselves.