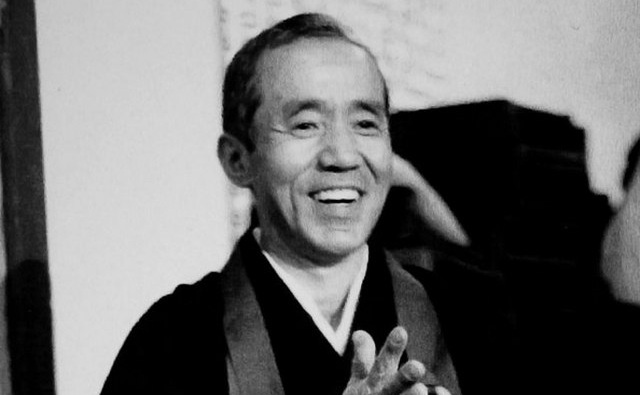

We’re back with Part 2 (out of three) of my reflections on my father. I should mention that this was written for a mostly Buddhist audience, which is why a few of the terms will likely be unfamiliar to you. I’ll save you the trouble of Googl-ing them for yourself.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

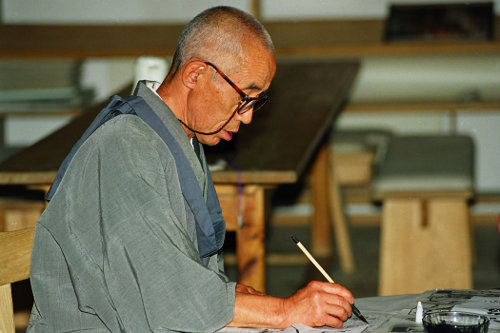

My father had a study in his home. Actually, I believe it was more of a large closet that was converted into a study. Inside the small room a zabuton and zafu were positioned in front of a low table. On and around the table were a collection of writing supplies, brushes, inks, paper, and lamps. But what dominated the space were his books. He had what seemed like thousands of books arranged in stacks, placed on shelves, resting on the table and under the table. There probably was a system, but it remained a mystery to anyone other than himself.

This small room was simultaneously his private zendo, library and art studio. And while he didn’t stay in permanent seclusion, it was not uncommon to find him toiling away over parchment, painting or tome at any time of day (or more often night). I used to think it strange that he would spend so much time cloistered away. Now I understand that there was something sacred about that tiny sanctuary, and I find myself attempting to re-create similar rhythms and spaces, hoping to find a small place of respite inside an otherwise busy home and an otherwise busy life.

This small room was simultaneously his private zendo, library and art studio. And while he didn’t stay in permanent seclusion, it was not uncommon to find him toiling away over parchment, painting or tome at any time of day (or more often night). I used to think it strange that he would spend so much time cloistered away. Now I understand that there was something sacred about that tiny sanctuary, and I find myself attempting to re-create similar rhythms and spaces, hoping to find a small place of respite inside an otherwise busy home and an otherwise busy life.

If he wasn’t in the study, the next most likely place to find him was in the kitchen. He gave careful attention to the preparation of food and was a remarkably adept cook. Much like his religious beliefs, he took the cuisine of his ancestral heritage and adapted it for a new cultural setting. Rice was a non-negotiable, but it was always served with some other traditional Japanese dish that typically included some of his own improvisations.

Of all the food items he prepared, the “rice-ball” will be the one that remains forever etched into my memory. It’s simplicity, portability, and novelty has no rival. Anytime I was traveling some distance, without fail he would send with me a couple of seaweed wrapped balls of rice that were slightly larger than my fist. Which Japanese pickle I might find pressed into the center of this ball was always a surprise, but the pungent flavor of the umeboshi was undoubtedly my favorite.

While I believe he found great pleasure in giving himself to the mysterious intermingling of truth, beauty, routine service and compassion that was to be found in the study and kitchen, he seemed most at home with himself when he was outside enjoying nature. It mattered little if he were spending a couple hours (or nights) bivouacked by his perpetually under-construction house, wandering the slopes of El Salto, or gracefully gliding down the snow covered mountainside. There was something about being close to creation that breathed life into him.

While my father enjoyed interacting with people in certain times and places, truth be told I think he found verbal communication taxing. He could be wonderfully clever and profoundly ambiguous all within the same breath, but in day-to-day life he could allow hours to pass with little to no talking. Indoors, silence can be strange. But under a canopy of trees, with the soft earth underfoot, being quiet seems the normal thing to do. Which is perhaps why he seemed more at home and more himself when he was outside.

“The joys of parents are secret, and so are their griefs and fears.”

Francis Bacon