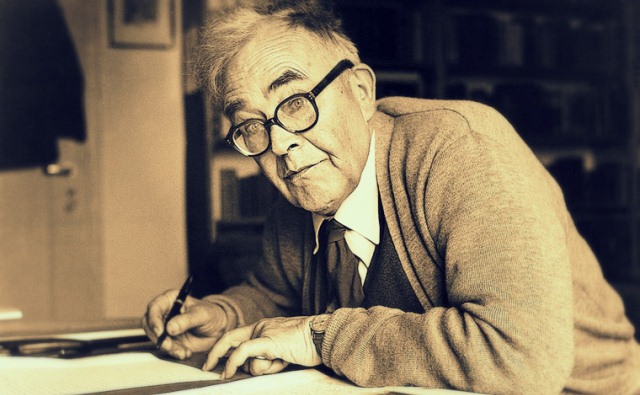

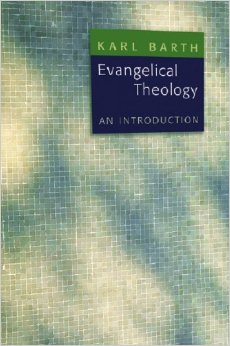

And we’re back. Even though you have had a two month break from my half-baked musings on Barth’s Evangelical Theology, rest assured I haven’t been on a Barth-break. For me, it is all-Barth-all-the-time. This is neither bragging or complaining, but a recognition of what a wonderfully odd life I lead right now. Today, we’re taking a stab at his understanding of ‘faith’.

The chapter itself is fairly straight-forward. Barth’s spends the first half clearing the ground of detritus that masquerades as faith. A person’s having weighed the evidence and determined that ‘faith’ is the most reasonable option. No good. Faith as an assent to a set of propositional truths. Also, a no go. People becoming part of the divine essence through faith. Nonsense. Faith in faith. Laughable.

But that isn’t really what I want to talk about. Nor is it really what Barth wants to talk about either. Barth will go on to describe faith as an event, and if that thought is intriguing to you (as well it should be) then you can go read the remainder of the chapter. My thoughts from here are more of a riff on Barth then an attempt to ‘faithfully’ reproduce what he’s said. The question I want to consider for a few hundred words is the apparent dichotomy between faith as divine gift or faith as human response. Or to put it in slightly more crass terms, is faith something God does or something we do?

Now regardless of which end of the theological spectrum a person find him or herself, this isn’t a trivial matter. Huge questions regarding divine sovereignty and human responsibility lie in the immediate background. So some folks will read the scriptures and pick up on the strong emphasis on God’s sovereign faith-giving initiative. Certain passages from Paul’s letters lend themselves very well to this understanding. Others are uncomfortable with this overly-deterministic perspective and favor instead the scenes in the Gospels which depict a person making a choice to follow Jesus – or not. This conversation has a very long history and I don’t pretend to think that I have anything to contribute in that debate.

However, I do think that Barth’s language of ‘event’ and ‘encounter’ provides an opportunity to move beyond the stalemate that is, in fact, stale. God’s self-revelation in Christ (as mediated through scripture and proclamation) means that God chooses to freely disclose himself to the individual. That is to say that God takes the initiative. In that event of God’s self-presentation, the individual is freed to respond freely in faith. Again, not faith in some vague generalized sense. But faith in a very specific object – the God who has revealed himself in Christ. This preserves so much of what one wants to say about the dynamics of faith. God is the source and the object of faith. Humans cannot muster up faith on their own, but in the divine encounter they do really and freely respond in faith.

Now, I say freely. But that suggests that they might have been able to choose otherwise. That isn’t quite what I’m saying. Perhaps a weak analogy will be a help here. Suppose one of my children is in the bottom of a well with no hope of climbing out. They are stuck there. Then all of a sudden good ole’ dad shows up with a ladder. I stick it down the well, climb in, tell them to jump on my back, and climb back up. Ok, lame – I know. But the key bit is that it took ‘faith’ for him or her to climb on my back, right?

Now, in this scenario it is a little silly to ask where the faith came from. Did I give them the faith? Did they generate the faith? Those kinds of questions seem to miss the point. I showed up, and that’s decisive. My showing up prompted them to have ‘faith’ in my carrying them out. And yet, one could say that I gave him or her faith by my showing up. If I hadn’t come then they wouldn’t have had cause for faith. Likewise, was it a free action on their part? Well, of course. Did they have the freedom to choose otherwise, I suppose so. But not really. Just because they had no alternative but to trust me doesn’t mean that their ‘decision’ to trust me wasn’t a free one.

Of course, the analogy breaks down in all sorts of ways, but the point is that the necessity of faith doesn’t in any way diminish human freedom. In fact, Barth makes the point that it is in this very encounter that a person is made free for faith. Unless God shows up, a person is stuck. Neither free, nor free to choose freedom. But whenever God shows up on the scene, he has given the gift of himself. And as someone once suggested, “if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.”